Light Up Your EDC with the Right Torch

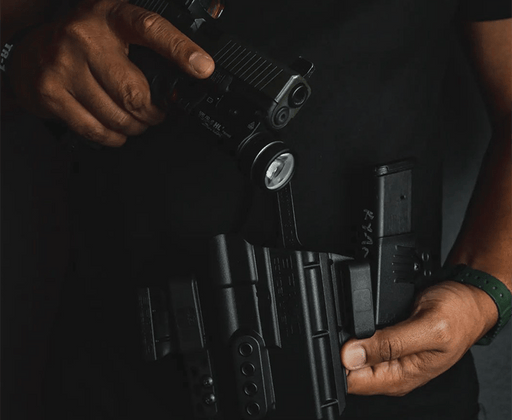

Regardless of how perfect your gun and holster are, an everyday carry (EDC) setup falls short if you don’t have access to a good handheld light. My definition of a good handheld light is one that’s intuitive to operate and bright enough to identify objects in a visitor’s hand in a hurry, across whatever space in which the light is deployed. Here are some criteria I follow for light selection for personal and property defense.

Start with Reliable and Simple

Sure, you’re going to use your light for lots of things, self-defense probably being least among them. But just as I selected my EDC gun based on confidence that it’ll work when it’s called upon, with a minimum of fussing with mechanical features, a light that’s owned for the purpose of covering Safety Rule #4: Be sure of your target and what’s around it, should be selected with the same criteria.

Let’s talk about reliability. Select a light that has an aluminum, not synthetic or rubberized, case. Pick a brand that has a wide record of use with American police agencies. That list, as I know it, is pretty short. Consider Streamlight, Surefire, Nightstick, and Fenix. Yes, there are others, one of which is gaining acceptance with EDC types. However, I’ve not included this popular choice because of the number of random failures I’ve seen in these lights. Hours before I wrote this, a European-brand tactical flashlight that I’d become pretty fond of rolled off a six-foot shelf in my home and hit the tile floor. It has a rubberized synthetic case, nice for use in cold weather. It was not so nice when a hunk of bezel (the shield around the lens, staggered on many tactical flashlights to double as a striking tool), broke off and the internals of the switch got stuck permanently in the “on” position.

Some outlets, like LA Police Gear and First Tactical, have sub-contracted with light companies to vend their own store-branded lights. Naturally, it’s usually not possible to find out the real brand of such lights. I’ve had both good and bad luck with such lights—consider these a secondary choice worthy of trying out as a backup. Such lights should earn your trust with time and use, store brand notwithstanding.

There are some great lights out there, often called camping or survival lights, that are wonderful for backcountry (or backyard) outings but less than ideal for self-defense. These lights might have a red setting for reading, a blue light for tracking, various white light settings, a strobe, and an SOS blinker, all operated with one switch. While I’ve had my turn laughing at shooters who show up for class or a qualification with one of these lights, frustrated as they cycle through all the functions in a search for a beam that’s enough to see the target, it would be no laughing matter to be in the same situation when faced with a real threat. Seek a light with a maximum of three or four settings, i.e. very bright, low, and strobe. Save the camping light for camping/hunting.

Switches Matter

In a self-protection situation, you need to handle the light with ease. A good tactical light that I’d choose has two switch features that make it a veritable “easy button.” For ease of use and good tactical consideration, select a light that has a tailcap pressure switch. As the name suggests, a tailcap switch is located on the rear of the light, so when you grab it in a fist, the thumb naturally meets the switch. There’s no wasting time rolling the cylindrical housing in your hand, searching for the switch. This is what I’m referring to when I speak of the light having an intuitive interface.

Of great benefit on that same switch is pressure-sensitive operation. Pick a light that goes on with thumb pressure and off when you release. Of course, press it harder and it’ll click to the “on” position and stay there until it’s clicked again. A pressure switch is a bit of insurance, especially if the light is dropped and inadvertently lights you up instead of the threat. It also helps conceal your location with its silent operation. Should the light be pressed just enough to see an imminent attack, it’s easy to release the switch, step aside into darkness, and execute a plan to escape or come out fighting if necessary when the light is back on. Darkness, after all, offers its own kind of concealment, something criminal actors exploit all the time. Feel free to do the same.

Brightness is Rightness

If you think your big-box store light or phone light is enough, spend a buck on a paper target showing a “bad guy/woman” wearing typical burglar/home invader garb—a dark sweatshirt. Turn your light on that target across the bedroom, the garage, the backyard, or wherever you go on the regular after hours and won’t draw attention by virtue of the exercise. Can you see the weapon in the hand of the person pictured on the target? This is the test—at the distance of seven yards on the nighttime range—that has yielded many crestfallen faces when shooters realized their Big Store Tactical light wasn’t up to the job.

In a small living space or space that’s aplomb with windows and mirrors, 300 lumens is usually adequate for target ID. That level of brightness also represents affordability. If you look hard or shop sales, it’s possible to nab a great 300-lumen torch for less than $45 as of this writing in April 2022. If your budget is broad, and certainly if your physical area of responsibility is, i.e. a church or office, large residence, or farm, it’s time to spring for at least 750 lumens, preferably more, and the batteries to feed that power.

Power for More Than an Hour

The brighter the setting, the longer the use, the shorter the battery life. Like buying ammo for your gun, part of your light budget should include at least two changes of battery. Lights that run on typical batteries available at any convenience store can be just fine, and are easy to replenish for most people. However, the brightness that comes with larger batteries like the CR123A is undeniably superior. And the batteries aren’t cheap. Keep a supply of fresh batteries on hand; you’re going to need them.

Rechargeable batteries are an option, and can be a handy one. I’ve benefited from having backup CR123A batteries from Ready Up Gear that rechange with a micro USB in my car. The batteries are easy to keep on hand in their protective case, and lots of people have a micro USB cord on hand anyway. The quality of rechargeable batteries has improved greatly in recent years. However, they are known for being limited in the number of recharges they can take before developing the problem of draining rapidly when in use. It’s just another option; all choices of battery have their limitations.

The C part of EDC

Just like a gun, the light you leave in the nightstand can’t help you when you’re crossing a dark parking lot. Have more than one light, and have them staged at easily accessible locations if you can’t commit to carrying one on-body. I have two lights at all times in my vehicle—a primary and a backup or loaner, several inside the main entry to my home, and one by the bed. I’ve been surprised at the number of times I’ve loaned a light to someone who had none, on and off the range. I’m also comforted knowing that the light doubles as a striking tool in my non-primary hand.

A previous article covered shooting with light in hand, a necessary skill for any serious concealed carrier to develop. Staging lights where they’re easily accessed, in your home, vehicle, or on-body, is almost as important as figuring out what kind of holster to choose and where to wear it. When the light is in-hand but not in use, consider using a wrist or fairly loose thumb or finger loop to prevent losing it. That loop should be slack enough that the light is easily separate from your body if someone grabs it. Never allow the light to be a handle for an attacker to drag you.

Readiness to light or fight

Many lights have clips that secure them to clothing. Clip it on and practice drawing the light from your non-gun side just as you’d practice drawing your pistol. If you’re in a setting of changing light conditions where some places have sufficient light but it’s needed when moving into a nearby space, make a habit of carrying the light in the support (non-gun) hand held in a fist, thumb up and lens pointing toward the ground. Carried this way, the light is easy to deploy for using alone or with a gun. It also puts your elbow and the light itself in a place where you can physically block an incoming punch or, better yet, a position of advantage to use your elbow or the light defensively.

Using the light as a weapon, if necessary, is of course enhanced by practice. It doesn’t hurt to spend a little time on a real or improvised punching bag, practicing explosive strikes with your light in hand. Practicing such strikes is not unlike practicing shooting. It’s okay to school yourself to consistently hit a small target the size of, say, an adult’s nose. But in practice, don’t hesitate to strike broader targets like collarbones or, less preferably, a neck. In practice, a punching bag or improvised target moves more or less predictably. Real opponents don’t. Planning to hit a small target like an eye or temple is great for developing technique, however the likelihood of a miss is substantial—not to mention targets on the skull are out of reach for some smaller-statured people.

Of course, some lights are so small in comparison to the user’s palm that this advice may not apply. Use common sense.

Maintain your light

Even if you’re not using the light every day or every week when it’s on your person, turn it on at least once per wearing. Check that the beam is good and bright. Even weekly use will help prevent battery leakage, which can “kill” any light regardless of quality or purchase price. Just as with your firearms, monitor your light’s features on the regular. Wipe off the lens and housing to maximize brightness and clear any accumulated grit or rust that may interfere with the switch.

If battery leakage has occurred inside the light, as indicated by the presence of a chalky white substance, tap out any that gravity will yield, and swab the inside of the light with a clean, fuzzy cloth or cotton swab. Batteries left idle tend to leak, so if there’s a light that’s being saved for a special occasion, store batteries separately until it’s time to use them. Leaky batteries have ruined many a good light.

Get a great light---or three, or four. And carry them in good health and with pride that you’re more capable of helping yourself or another person in need by lighting the path ahead.

Leave a comment