Do you find yourself having to reset your support hand after almost every shot? If so, it’s time to examine the topic of grip. Grip is one of the Seven Fundamentals of Marksmanship, and, especially when firing more than one shot, among the two most important. In other articles, I’ve discussed proper gun handling in terms that address grip. This article will go deeper to address the usual mistakes I see related to grip, and how to prevent them. Here, we’ll address how to be sure your grip is not too loose or too tight, and how to determine when it’s just right.

The basic practice of a good, firm grip does not come exclusively from finger tension. “But my hands aren’t strong” is a common reason new shooters give for thinking they won’t shoot well. Though strong fingers help, weak or injured ones can grip just fine. As you read the following instruction, think of terms like “firm” and “solid” as coming from pectoral (chest) and forearm pressure, not from the fingers. One of my clients lost her trigger finger as an adult and still shoots her full-size 9mm semiauto very well. Another is missing the thumb of his primary hand, and shoots a variety of semi-autos and revolvers, large and small, safely and accurately. By using safe handling practices and good technique, they do just fine, and so can you.

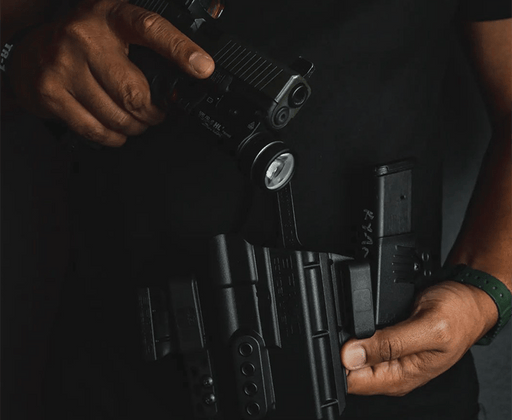

Primary Hand

The primary (trigger finger) hand should go as high as possible on the backstrap. Doing so places the barrel and the long bones of your lower arm in as close alignment as possible when shooting. This minimizes recoil by reducing the fulcrum effect between the gun and operator.

That high grip recommendation is assuming you can reach and use the trigger from there. For some guns, depending on your hand size, you may need to lower the primary hand just enough to reach it.

With the trigger finger straight and on the frame, close the lower fingers snugly around the grip. They shouldn’t be wrapped so tight as to be white-knuckled. Your trigger finger needs to be able to feel its way around the gun and trigger, after all, and there’s no reasonable way to tense the other fingers while keeping the trigger finger nimble.

The thumb should be against the frame, maybe also touching the slide. It should point in same approximate direction as the muzzle. If you’re shooting a 1911, the firing hand thumb should ride above the slide safety while firing for both efficiency and to prevent accidental engagement of the safety. If you have hands that are on the lower 50% of the human hand size spectrum, it may be necessary to allow this thumb to ride under the slide safety.

Support Hand: of biscuits, pushing, and pulling?

The support hand is often ignored but it actually has a bigger job than the firing hand.

The support hand is often ignored but it actually has a bigger job than the firing hand.

The support hand should be placed with the four fingers touching, not fanned out, index finger in contact with the trigger guard above.

On semi autos, the support hand thumb’s lowest joint should do the spooning thing (yes, I mean “spooning”) under the same joint of the primary hand thumb. Both thumbs should point in the general direction of the target. Do not put the support hand thumb next to the other; put it underneath so that both palms and both thumbs are in contact with the gun. Assume a firing grip (finger off trigger, of course) and look at your hands. If the backs of your hands resemble butt cheeks (yep, I mean it), advance the support hand forward so its palm is on the grip of the gun and on the nails of your lower three fingers.

In short, your support hand grip needs to be tight; tighter than the firing hand. But I don’t mean tensing up the fingers. Accomplished competitor and fabulous instructor Ron Avery, now sadly deceased, had an unforgettable way of describing what to do with the support hand. He’d remind us that the palm of that hand has a texture not unlike a raw Pillsbury biscuit, right out of the can before baking—you know, the kind that makes you jump when the can pops open. Imagine your support hand palm is a raw biscuit. Now imagine what it would take to put that biscuit on your bathroom mirror in such a way that it sticks there and doesn’t fall off. For sure, there could be no air pockets under the biscuit, or it’ll hit the counter. And you have to press that “biscuit” against the gun using the big muscles of the chest and forearm while not overdoing finger tightness. That is what you need to do with your support hand. Do that, and you should enjoy better recoil control as well as not having to reset the support hand after every shot.

In combination with the above, some people find it beneficial to think of pushing the gun straight into the target with their firing hand, while simultaneously pulling it straight back to the chest with their support hand. I personally use this method but my partner, who’s a fantastic shooter (and physically much larger), doesn’t find it beneficial. What is for sure is that everything I just described in the preceding paragraphs works regardless of your stance preference.

Should the index finger of the support hand go under or in front of the trigger guard? Some prefer hooking the index finger around the front of the trigger guard. A fair number of trigger guards are shaped so as to encourage this. It’s a technique that’s phased in and out of vogue over time among the competition set. And while it may have some benefit for recoil reduction when sufficient rearward pressure is applied to the trigger guard, it’s my opinion that it’s not the best technique for defensive shooters, for three reasons:

Should the index finger of the support hand go under or in front of the trigger guard? Some prefer hooking the index finger around the front of the trigger guard. A fair number of trigger guards are shaped so as to encourage this. It’s a technique that’s phased in and out of vogue over time among the competition set. And while it may have some benefit for recoil reduction when sufficient rearward pressure is applied to the trigger guard, it’s my opinion that it’s not the best technique for defensive shooters, for three reasons:

i. The benefits of a technique dependent on finger strength only last so long. Unless the operator’s fingers are remarkably strong, the recoil-taming effect will fade with fatigue. As for my own grip, I can feel the relatively powerful grip of having my support hand fingers arranged as recommended under the heading “Support Hand” above. Using this method, the “meat” of my hand lends its best effort. When fingers are split, so is grip strength.

ii. Digits that stick out are not conducive to gun or bodily security. If you’re in a situation where violence runs amok, chances are someone will want to grab your gun. The reduced overall strength lent by a split-finger grip, along with the presentation of a body part (an index finger) that’s now easier to grab, use as a painful lever, and the subsequent release of the gun, are enough to motivate me not to stick it out around the trigger guard.

iii. Accuracy at distance may be needed. When firing at distance, it doesn’t take much error to throw a shot off a torso-size target at 25 or 50 yards. A finger hooked around the trigger guard will almost invariably exact lateral deviation upon the muzzle, resulting in a miss, even if the deviation is slight.

Fool Around and Find Out

What I’ve shared here are grip techniques that many uniformed students have told (and shown) me made the difference between being able and not being able to make the time limits on their shooting qualifications where multiple shots are required. For sure, most people don’t give the support hand enough credit for having an important job. When shooting with two hands, the support hand exerts greater pressure than the firing hand. This minimizes muzzle rise in recoil and increases overall control of the gun. And that makes for a more pleasant shooting experience and the ability to go faster if you want to.

Leave a comment

1 comment

Very informative. I will try relying on the fore arm and chest to squeeze on the support hand and not only relying on the support fingers. Thanks